Opening Photo: Isonnette, Glow, Joel, Jessica, and Aiden wade out to remove cattails that are out-competing other wetland species.

This past Friday, two dozen Common Ground students showed up after school to care for the educational wetland on our campus. Four teachers were on hand to help, but Isonnette O’Brien – who last year as a 10th grader founded our Wetland Crew – was the natural person to lead the opening circle. Icy started by making sure we all knew each other’s names and pronouns; it’s the start of the school year, and while many in the circle had spent dozens of afternoons at the wetland, many others just joined our school community. After that, she thanked students for volunteering their time to care for this beautiful oasis on our campus, helped us organize ourselves into work groups, donned her waders, and led the way out into the muddy waters.

Deep Waters

The wetland that Isonnette and her fellow students steward is fed by runoff from the slopes of West Rock Ridge State Park – and also by a stretch of PVC pipe emerging from a stone headwall just uphill from where Icy waded in. Elders in our New Haven community tell us that neighbors and visitors have been coming to the spring on Common Ground’s campus for as long as anyone can remember. Common Ground’s retired custodian, Melvin Griffin, describes parties that ran late into the night, and cars that traveled from as far away as Pennsylvania to fill milk jugs with the healing waters. Amateur student and staff archaeologists have found rusted beer cans and glass jars that tell a similar story. We guess that the natural spring for which Springside Avenue is named has been a gathering place for far longer – likely for the Golden Hill Paugussett and other Native peoples who stewarded this place until colonizers forced them off the land, which they became a small farm, and then city parkland, and then Common Ground’s home.

When Common Ground’s first students and staff came to our site in 1997, the spring was no longer much of a gathering place. They uncovered the springhouse and headwall, like the rest of the site, from years worth of multiflora rose and illegally dumped garbage. The health department advised these early Common Ground community members against drinking from the spring, at least not without repairing the old springhouse first. And the water which used to run year round now dries up in the summer – the result, we fear, of the same changing climate that causes so much flooding and erosion on our campus.

Opening and growing a small environmental charter school and community organization meant plenty of distractions from keeping the multiflora rose at bay. And so it took until around 2010 for Common Ground to start making serious plans to renew the spring as a community center. Samantha O’Brien – no relation to Isonnette, then a Common Ground student and now the head of the science department at a Bay Area charter school – worked with environmental leadership manager Rachel Gilroy to draft early plans for better stormwater management on our campus. Their plans included a wetland near the spring, and the idea got momentum when Sam and other students wrote and received a $100,000 grant to help enact student-designed sustainability projects on our campus. Our students and staff started work to design and build a new school building – called Springside – and to create a wetland and other green infrastructure features that would help manage stormwater and reduce pollution reaching the West River and Long Island Sound.

Losing Javier Martinez, and Growing A Place To Keep His Memory Alive

Our plans for an educational wetland took on a whole new meaning in winter of 2013, when we lost Javier Martinez – one of our seniors – to gun violence. Javier was a sweet, funny young man who loved big meals with his friends, took pride in his sneakers, and played Oedipus in a class play. Javi was also a really powerful environmental leader. You can visit 50 street trees all over New Haven that Javi planted with the Urban Resources Initiative. He spent the summer before his senior year out on Martha’s Vineyard, interning with The Nature Conservancy. There are pictures of him in waders, just like our student wetland crew, mapping storm drains along the West River downstream from our campus.

Javier Martinez out in the West River. with a fellow student and Green Jobs Corps member, Lorenzo,

Losing Javi was the hardest thing that had ever happened to our Common Ground community. Between Christmas and New Year’s, we gathered with his family in our school cafeteria. English Teacher Joan Foran brought cookies shaped like sneakers, and a copy of the essay Javi wrote about his hopes for a city where his siblings and nephews didn’t have to face drugs and violence on a daily basis. Larry Dome, Javi’s guidance teacher, tried and failed to hold it together while talking about the young person he loved. Liz Cox, our school director, asked Javi’s family what we could do to help us heal, and they talked about creating something green and growing in his memory.

That Spring, our students and staff worked with Javi’s family to create the Javier Martinez wetland. Seniors sat down with Landscape Architect Mark Papa to create the plans. Students in Common Ground’s Biodiversity class planted a hundred plugs of Bullrush, Duck Potato, and Woolgrass. One Saturday, nearly 100 people came out to plant shrubs and trees around the wetland, under the guidance of soil scientist David Lord. One of the most healing moments I’ve experienced happened that day, watching Javi’s aunt and grandmother wash their faces in the spring, and looking out at the place they’d created in his memory.

Javi’s family and friends join Common Ground staff and community volunteers on a big wetland planting day in Spring 2014.

It rippled out from there. Some of Javi’s classmates learned about research showing that neighborhoods with more trees have less violence; they reclaimed the spot where he was killed by planting a tree there, and started a campaign to raise awareness about the connection between greenspaces and violence prevention. Another group of students worked with residents in Fair Haven, the neighborhood where Javi lived, to dedicate a community garden to his memory. A third group of his classmates organized dinners and basketball games where young people could come together in peaceful, positive ways. What these young people did led New Haven’s mayor to start an youth anti-violence initiative that helped reduce our city’s homicide rate substantially, and led one of our senators to bring Javi’s story to the floor of Congress.

I bet that other communities find their own vocabularies to describe their love and loss, and other ways to heal from their grief. For Common Ground, it feels right that we spoke our pain and our activism through trees, and gardens, and food, and water, woven through with basketball, and sneakers, and laughter, and tears. This, for me, is what urban restoration looks like: people putting themselves, and their community, and their places, back together, together.

The Student Wetland Club

It’s been more than ten years since we lost Javi. Though only one or two of our current students ever got to meet him, many still feel a deep, sometimes fierce sense of care for the wetland we created in his name.

Isonnette describes finding the wetland – “a beautiful, peaceful place for me to come” – before she heard Javi’s story. She learned a little about the origin of the wetland in Sierra Dennehy’s 9th grade biology course, and started doing her own research. “Hearing Javier’s story was heartbreaking. As a person of color, seeing gun violence impact someone who shares my background is really hard. Knowing that CG built the wetland in Javi’s memory was really beautiful, and helped me understand that Common Ground is a community. Seeing the wetland deteriorate, and not look as pretty as it could, wasn’t o.k. with me.”

So Isonnette decided she didn’t need to wait to be a senior to start the capstone project required of every Common Ground graduate. She asked teachers, and persisted until she found an advisor – environmental educator Morgan Larson – to support the club. I and others helped identify the resources to pay them through an EPA environmental education grant. But Isonnette and her peers were the driving force. “I definitely asked a lot of my friends. I spread the word about Javier’s story, and the wetland. Other people agreed. They want it to be a resource, a beautiful place, too.”

The wetlands club met weekly throughout Fall 2023 – sometimes with a score or more members, sometimes a half dozen. When Morgan moved on to a full-time job at another organization, Icy and her team regrouped, and Wetland Club merged with our school’s Green Team to run throughout last year. This past Friday’s planting day was a very good sign that the wetland crew will only grow in the year ahead.

When I join the wetland crew, I’m most struck by the joy, the conversations, and the inclusive community there. I am guessing that young people show up for the relationships, for a space where they can be their whole full selves, at least as much as they do for their love for the environment. Isonnette has great fashion sense; I’ve watched with concern and then awe as she took on a massive multiflora rose while wearing flower print overall shorts and matching Converse. Like Icy, many wetland club members wear their personal style with confidence and pride, and definitely don’t feel a need to follow any stereotype of what an environmentalist or environmental professional might look like. It’s a space where students’ gender identity, sexuality, race, disability status, and personality don’t need to be dialed back or seen as a barrier. These things that make us who we are just add to the power and coherence of the crew. Every day I work with them, these young people teach me that It’s impossible to separate environmental justice from social justice, community from place, human healing from environmental restoration. Why would you even try?

When Isonnette talks about what she’s most proud of about the wetland club, she describes the community – “how brought together we are.” She explains, ”Even if we have to get in the water, we are happy about it. They make it fun to clean. Even if someone is upset, or isn’t feeling great, they still show up to be part of it. They show what a community is.”

When I asked about moments from the first year of the wetland crew that stick with her, Isonnette described the day they installed an interpretive exhibit at the site. The exhibit was the brainchild of another student leader – Deja Beckford ‘23 – who learned to love the wetland through Common Ground’s Biodiversity class. Deja was inspired enough by this environment and its story to focus her senior project on this place, and did the intensive research, project management, and collaborative design work necessary to create a professional, engaging outdoor exhibit. Deja was motivated in an important part by learning about the exclusion of other African Americans from the conservation community – she wanted to create something that would help the racially diverse community that comes to Common Ground connect with nature, just as she has. This wasn’t just a project for Deja; she is now studying biology and environmental science at UConn; this summer, some of our staff ran into her helping to survey trees at a nearby park.

Emma, Brandyn, Isonnette, Leon, Claire, and Morgan after installing the exhibit designed by Deja Beckford ‘23.

Part of the power of Javi’s wetland is that many environmental leaders can make it their space, as Deja did. Leon Armstrong ‘24 used mugwort gathered from around the wetland as the warp and weft for a community weaving project – bringing together his friends with neighbors experiencing homelessness to build relationships while creating woven art together. Jessica and Ellyn have noticed a viscous rainbow on the water near the headwall of the wetland, and are tracing it back to its source – perhaps the drainage grate next to the blacktop up the hill. Brandyn wants to create a sculpture of fallen trees to hold the messages that Javi’s friends and family wrote ten years ago on metal tags, so they don’t cut off the circulation of growing trees. The wetland has motivated student leadership from the start; AP environmental stience students were worried about shifting frog populations, and started a campaign to save the wetland – within a year of its initial creation. Our students care deeply about climate change and other global environmental challenges; many of them choose to respond to it at this intimate scale.

This Is What Environmental Leadership Can Look Like

Much of what makes the wetland crew so special – and such a powerful model for inclusive environmental leadership – was on display during this Friday’s work party. Brandyn jumped in during the opening circle to talk through how to keep yourself and the wetland creatures safe as you wade in. Another long-time crew member taught a first-timer how to keep a wheelbarrow steady. I saw a student who I believe is on the autism spectrum, who is incredibly academically motivated but often struggles with social interactions, connect with peers and adults around shared work in ways that clearly brought him and all of us joy. Two new 9th graders flirted and talked while shoveling bark mulch. The moment I let two newcomers know that I’d love for them to stay, as long as they could stop pushing each other, they stopped – it seemed like they knew they were part of something precious, and didn’t want to miss out.

After an hour in the water, Isonnette circled us up again to celebrate what our joyful, muddy crew had done together. Cattails – a native but aggressive species that has been out-competing other aquatic plants – were pulled back to one end of the wetland, creating an open pool of water. We’d re-discovered and marked concrete piers put in when we first created the wetland, the first step in creating a platform that will let students and participants in Common Ground’s children’s programs get out into the wetland without getting covered in mud. Another crew had laid down cardboard and bark mulch in an area where mugwort and other invasives were shading out mountain laurels planted by earlier generations of student wetland stewards. (We decided to leave a few raspberries for future sweet treats, and to save our hands from thorns.) We closed the work party at 4:15, but students lingered longer – washing hands, helping put tools away, passing around mango body spray to cover a little of the earthy wetland stink, looking at pictures on each others’ phones, talking to each other. They eventually headed off to the bus stop, or to their parent’s cars – but I have a feeling they’ll be back. I know I will.

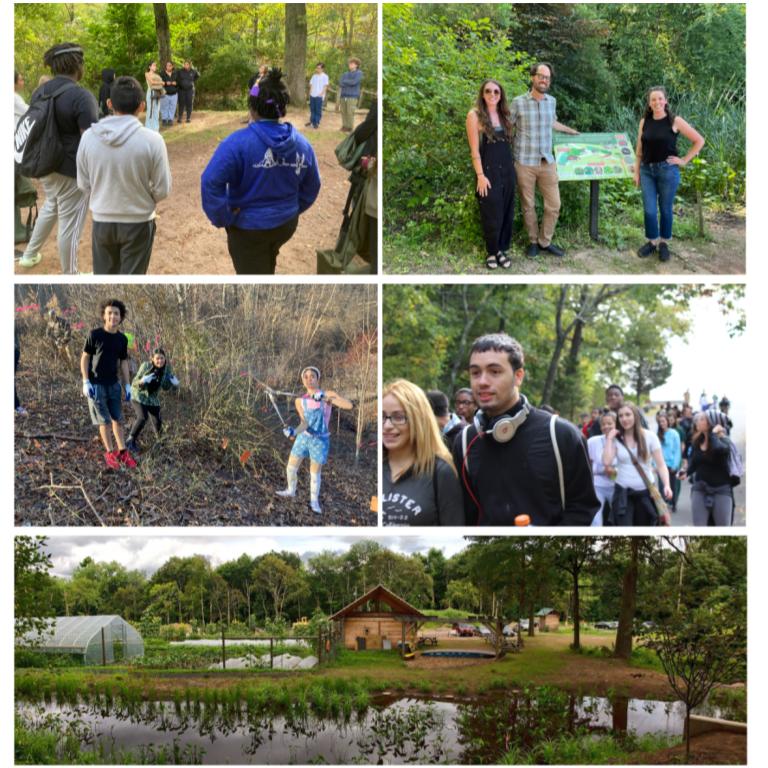

Clockwise from top: Isonnette leads the circle at our wetland club gathering. Sam O’Brien ‘12 (who helped originate the plan for a wetland on Common Groud’s campus) and Hailey O’Brien ‘14 (one of Javi’s classmates, who worked with other students to dedicate a community garden in his memory) return to visit Common Ground’s wetland. Javier Martinez on the all-school hike. The wetland soon after it was created. - photo by Domingo Medina. Isonnette, Glow, and Jose take on a multiflora rose during a wetland work day last winter.